Technology in the field of genetics is advancing faster than we humans can determine the benefits and ramifications presented by each potential use. This is why undertakings such as the Personal Genetics Education Project (pgEd) are imperative. Housed within the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, pgEd’s primary goal is to “increase awareness and conversation about the benefits and ethical, legal, and social implications of personal genetics.” Personal genetics is concerned with sequencing, analyzing, and interpreting the genome of an individual, or the unique code of DNA that affects health and appearance among other things. To better understand why it’s so important that not only doctors, but also every individual have access to information surrounding personal genetics, we had a conversation with geneticist and pgEd’s Director of Programs Marnie Gelbart, Ph.D.

PgEd’s mission is for all people to have access to information, and all voices to be heard in the conversation about how society uses genetic technologies moving forward. One goal is for people to have information about the potential benefits and ramifications of certain genetic tests before they are patients sitting in a doctor’s office in a vulnerable moment. Dr. Gelbart explains, “One of the front lines of genomic medicine is pediatrics — kids who are sick with rare conditions, sometimes conditions that have never been seen before.” It’s in these situations that doctors tend to run test after test in search of a diagnosis, and genome sequencing can replace or reduce some of that testing. Some tests may help find an answer, but it could also reveal information people may or may not want to know, such as a child’s predisposition to breast cancer, Alzheimer’s, or whether they’re biologically related to their parents.

Teaching people about personal genetics is not about encouraging them to get tested, so much as granting them agency. “I want people to be able to speak up for themselves,” Dr. Gelbart says. “To be very clear, pgEd doesn’t promote the use of genetic technologies, we promote access to information.” By encountering this information and considering implications prior to a vulnerable moment, people may feel more prepared for those moments.

Decisions about the use of genetic technologies is not only for individuals and families but also raises questions for society as a whole. Dr. Gelbart says, “Genetics has a horrible history of eugenics, which is a movement that started in the United States. Many groups of people were affected by this movement, which targeted people of color, women, people perceived to have disabilities, immigrants from certain countries, and those who were poor. Now as geneticists — as the people bringing these new technologies into the world — we have a huge responsibility to do anything we can for that not to happen again.”

One way to prevent one group from placing value judgements on certain genetic markers is to engage with as many different communities as possible. “A lot of that history inspired pgEd, and why it formed to engage our communities so that they also can weigh in on how these technologies are used going forward,” Dr. Gelbart says. The project is helmed by a small team of fewer than 10 people, and prioritization is sometimes a struggle in the face of such an gargantuan mission as educating the world about these new technologies. “We had a group of African American pastors come to Boston from Baltimore, and someone helping us orchestrate the meeting happened to be Muslim. At the end, he said, ‘That was a really powerful meeting, it’s great that pgEd wants to reach out to communities of faith, but why not the Muslim community?’ There is no answer, of course; why not? And actually, he joined pgEd so that he can help us start to work on that.”

In addition to programs that reach out to teachers and communities of faith, pgEd works to educate lawmakers. “We’re not there to advocate one way or another, and that’s the major reason we can get people in the room,” Dr. Gelbart says. “We’re not there to complain, lobby, or ask for money — we just want them to know what is happening in the space of genetics.” Speakers intentionally leave a lot of time for questions. This is done not only for Congress, but for all audiences, as, “That’s the best way to know what the audiences is interested in.” For example, while working with Muslim communities, an imam spoke up about genome editing being used in pig cells with the goal of making pigs a more suitable source of organs for transplant. “A choice of pigs could be problematic for Muslim communities,” Dr. Gelbart says. “That’s an important question and conversation about why that’s happening, and if there is any chance that kind of research will move to another animal. That can be really illuminating.”

In another example, she recalls work her colleagues are doing in underserved communities in the Boston area. “We often ask students about traits that they might want to select for their children. We could be in a room of black and brown students, and often at least one student will say, ‘blonde hair and blue eyes.’ For so many scientists, there are a lot of questions about the predictive value for those tests that are considered trivial, such as hair color and eye color. But I will say for communities where they are discriminated against based on their appearance, hair color and eye color are not trivial traits. There are safety ramifications, financial ramifications.”

This is why, Dr. Gelbart insists, it’s so important for pgEd to initiate conversations surrounding personal genetics. “For pgEd, education is truly two-way. We go in with something to share, and even more to learn,” she says. “It’s amazing how quickly a room can go from one where people come in, not sure if anything we’re going to talk about is relevant to them, to actually making very deep, personal, familial, and societal connections.”

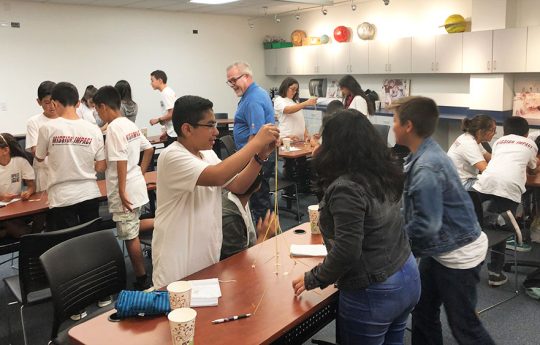

In May of 2016, pgEd was awarded a grant by the National Institutes of Health Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) program. One of the requirements for this grant was to have an evaluator external to the project. “I was very lucky to have met June [Bayha] at the National Academies of Science,” Dr. Gelbart says. “In her heart, June cares about doing good in the world, and she cares about the work, and making the work more effective, more powerful — that the work should come first.” The project involves developing curriculum geared toward high school audiences. There are professional development workshops for teachers and full lessons plans relevant to several subjects, including Social Studies, Humanities, Health, and Athletics. Bayha Group is developing surveys and measuring tools to determine the success of this program. “What we want is to put pgEd under a microscope and find how we can be effective in partnering with teachers in a meaningful way,” Dr. Gelbart says. “We’re entering our third year, and just starting to hear back from teachers who have come to our workshops. It’s still early on, but it’s really exciting. The teachers are amazing.”

Though she doesn’t spend much time in workshops on the “nitty gritty science details,” if there were one scientific point Dr. Gelbart wishes to convey it would be the idea of complexity in her field. The idea that one gene is linked to a disease, with a one to one relationship is “by far the exception and not the rule of how genetics works,” she says. This simplification can lead to inaccurate and harmful interpretations. “That complexity is a reminder that it’s not so simple to understand the genetic underpinnings of traits like intelligence. IQ tests were developed around the time of the eugenics movement. But there’s a complexity of measuring: what are the things we’re interested to know about people and how do we measure them? Are those measures capturing what we really want to know? Why are we not measuring empathy? Another thing we can measure is the influence of many genes in combination with the environment and microbes that live all over our bodies. We have as many microbes on our body as human cells, if not more. We are dynamic beings. All of those pieces are important for looking back at that history and thinking about how we go forward.”

Ultimately, pgEd’s aim is not for people to walk away with any one opinion, but to become comfortable having these conversations. “Our hope is people become more comfortable talking about genetics, speaking up, and asking questions,” Dr. Gelbart says. “To appreciate the diversity of opinions that exists on the topic of genetics. Maybe not agreeing with everyone in the room, but coming away respecting people in that room, knowing they do not all agree. Our goal is not to convince people to use genetics, and not to dissuade them either, but to give them information and let them decide.”