When explaining what it means to co-design with youth, Equity Designer Corrina Hui says, “We ask youth what is working for them and what is not. Decision-makers are in closed-door rooms trying to solve dilemmas for kids. Youth are experts of their learning—why are we not asking them?”

As defined by the National Equity Project, “Educational equity is the state that would be achieved if how one fares was no longer predictable by any social, cultural or economic factor.” When it comes to designing for equity, Corrina draws from her personal experience as a student of color who was accepted to an elite college preparatory school that was 80 percent white. As a first-generation Chinese-American in the heavily segregated Bay Area, Corrina had been used to attending school mostly with other kids who looked like her. It was at the prep school that she realized the difference between the curriculum she’d been taught, versus what had been taught to those who had been given access to elite private elementary and middle schools.

Despite excelling in math, Corrina surprised everyone in her life by choosing not to pursue the subject in college. “What I realized was, you can give kids all the academic support they want, but the missing piece, for me, was what nobody talked about: the racism and sexism at play, all those things that were causing me emotional distress. There were only two girls in my class, which meant every day, I’m proving girls can do math. It’s a disproportionate burden—my performance had to represent all of the women not present in that room.” Compounding those issues was the fact that Corrina was a slow and deep thinker in an environment where speed and fixed-mindset notions of success were rampant. For example, with team projects, she was left to face tasks alone because her group mates deemed her need to fully absorb information before contributing as “too slow.”

Corrina now realizes how designing for equity could have helped her when she was younger. “Teachers have design decisions every day,” Corrina explains. “If you have 40 problems you need your students to practice, you could put those 40 problems on one sheet, or you could put them on 40 color-coded index cards and hide them around the playground and make it an obstacle course.” This way, the students would still be solving the requisite number of problems, but doing so at their own pace (i.e., having the ability to choose the difficulty level of each problem they find and solve thanks to the color-coding).

“Teachers are designers because they have opportunities like this,” Corrina says. “It’s the same with the classroom—some have four rows of perfectly straight desks with 10 columns, all facing the front of the room, where the teacher is centered. In my classroom, my students used the design thinking process to build their own desks.” Her students built standing-height desks, so they could stand or sit on stools. “This allowed the classroom to be flexible—sometimes we’d put two student-built desks together to form small groups, and other times, we’d push all the tables to the perimeter and sit in a circle on the floor.

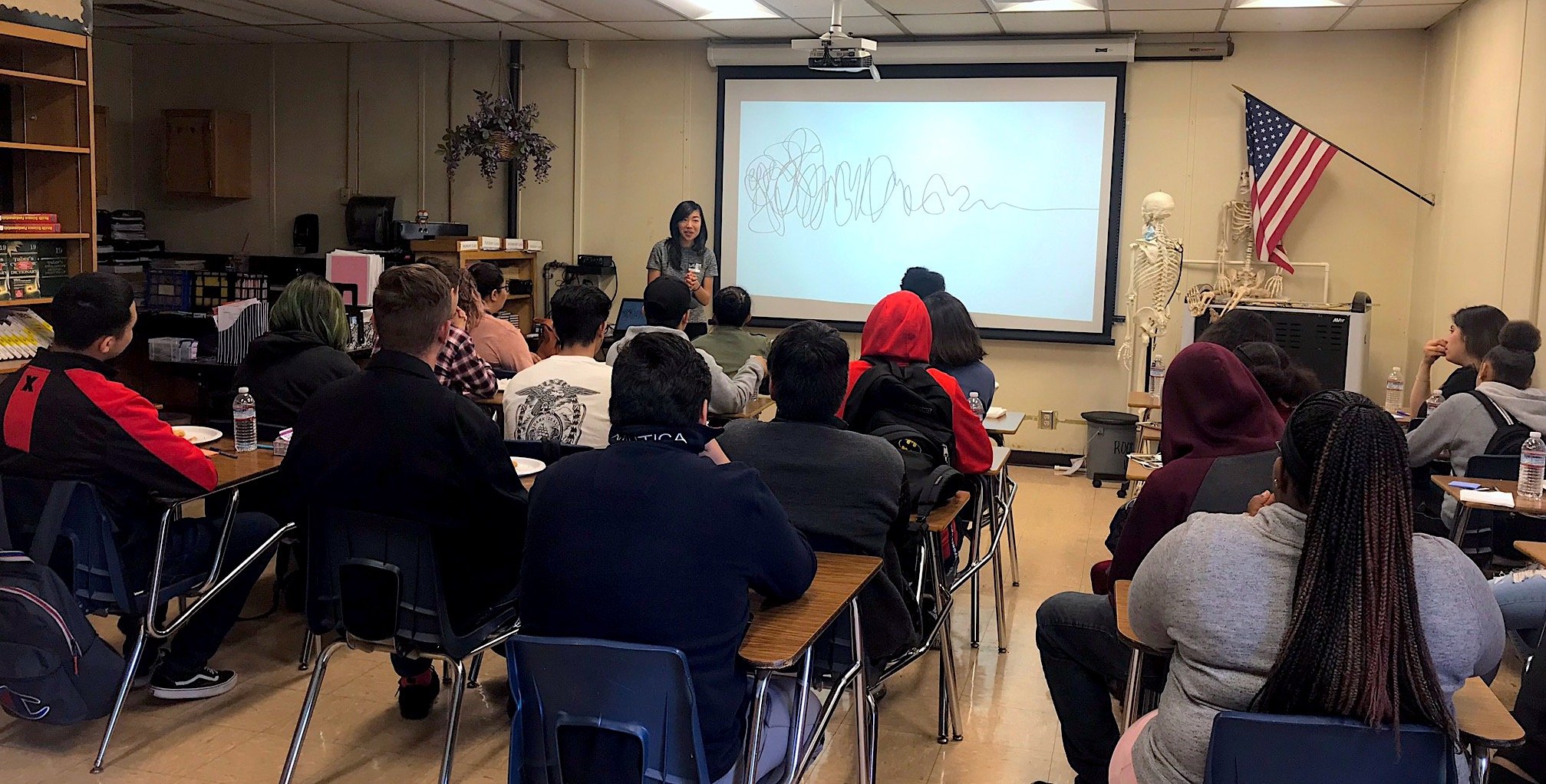

This Spring, Bayha Group is partnering with Corrina to bring her model of co-designing with youth to Southern California with a series of workshops made possible by the Performance Partnership Pilots (P3) project by the Southeast Los Angeles County Workforce Development Board (SELACO).

“We’re creating these experiences because we both believe in co-creating with youth,” says June Bayha. “It means really spending time to listen and to understand from their perspective what would be helpful and having them lead. There will be guidance, but overall, this whole project will be mostly directed by the very people we want to serve: a demographic known as ‘disconnected youth.’”

This five-workshop series will take place at Somerset High School in Bellflower Unified School District.

As an equity designer, Corrina approaches all learning environments from the perspective of these four tenets (though they are only part of her extensive toolkit):

- Self-awareness of who she is bringing (or not) to any person or context

- Understanding the effects of systemic oppression on the outcomes of design behavior

- Actively co-designing to interrupt oppressive structures like white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism

- Sharing the equity design practice toward a co-construction of the liberation of humanity

The way the current education system is set up is based on antiquated ideals that don’t fit with modern needs. “We’re training kids for the Industrial Revolution when what they really need in the Information Era is critical thinking, creative thinking, and the ability to be prepared for the unknown,” Corrina says. “If all you know are procedural skills, your job has already been automated. But that’s the capitalist argument. I’d like to turn it to the humanity and equity lenses.”

Corrina draws on lessons from history, such as the oppression and suppression of Native American identities, to the segregation that persists in contemporary educational institutions. “Thomas Jefferson in 1779 said that we should have a two-track education system—one for the laboring and one for the learned. Today, there is research that shows achievement on standardized tests are predictable by race and socioeconomic status. We have to consciously redesign, or else we’re perpetuating a system that’s working perfectly, exactly as it was designed.”

Corrina’s greatest hope for these workshops is to help students “recognize the systemic and institutional racism that have impacted their institutional journey.” She does this by helping youth discover their strengths, which have likely not been valued in their academic experience. For example, during a workshop in Oakland, she helped students realize that though they did not score well on tests, they were already demonstrating their keen sense of entrepreneurship and understanding of math by rushing to purchase new items by the popular clothing brand Supreme, and reselling at a markup so that they could afford to buy clothes for themselves. “By recognizing their strengths in a non-academic space, it gave them the courage to build new skills in the academic space,” Corrina says.

Though she will be facilitating discussions and guiding students throughout these workshops, Corrina says she plans to step out of the way as much as possible. “The students here are the experts. Let them present to you the journey they’re on and identify their purpose.” Helping students “identify their purpose” is a major goal of this project. And “purpose” isn’t just about identifying a potential profession to pursue, such as “doctor” or “lawyer.” Rather, it’s a recognition of multiple strengths that, upon identifying, helps students figure out what it is they want to contribute to the world.

“I want them to develop their intrinsic motivation,” Corrina explains. “I do that by holding space for them to notice the beauty in their lived experiences and stories, helping them see the inherent strengths they all have associated to those lived experiences, particularly those that have not been called ‘successful’ in schools. This will help them realize what the narratives have been, to recognize their internalized messages, like ‘you can’t,’ or ‘you won’t.’ We’re challenging the narrow definition of ‘success’ that is driven by white supremacy, colonization, and patriarchy in order to empower ourselves by understanding and redefining. These workshops will help students make the invisible visible so they can reflect and repair. They will have the opportunity to identify and challenge those messages, and have space to dream big and realize they are capable of doing whatever they want and that we are here to support them.”

To see how these workshops progress, stay tuned to our Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter account for updates, images, and video of this project, or visit this blog and Corrina Hui’s web site.